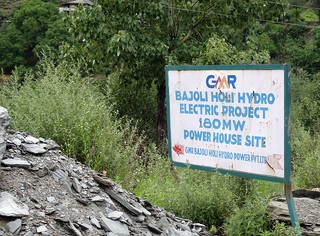

Small hydel projects are often hailed as sustainable models of power production but they spark an equal number of contentious issues much like the bigger projects.

As Hari Singh led me towards his fields, I wondered if he was trying to play a joke on me. Large rocks were scattered in the area and there was no sight of any arable land, neither was there any clue of the irrigation channel which Singh claimed ran through his farm.

|

| Hari Singh at his farm |

As Hari Singh led me towards his fields, I wondered if he was trying to play a joke on me. Large rocks were scattered in the area and there was no sight of any arable land, neither was there any clue of the irrigation channel which Singh claimed ran through his farm.

In the middle of the purported farm, he asked me to look up. I could see the mouth of a pipeline at a height of 40 feet. This was the spillover pipeline which releases excess water from the 2 MW Manimahesh Hydel Power project set up nearby. Every time water is released from the pipeline, it causes minor landslide thus dispersing rocks on 1.08 hectare of fields in the area belonging to six farmers of Saho village of Chamba district in Himachal Pradesh.

Obviously, this was not what company officials proposed when they first came to Hari Singh to lease his land. “They said a 3 foot diameter pipe will be laid under the ground to release excess water to the stream. I got Rs 1.75 lakh for the standing crop which was way less than the actual value. Later, to my horror they did not lay any underground pipe and started throwing water directly from a height.The money I got is nothing compared to the damage they have done to the land”, he said.

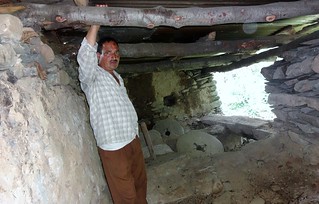

|

| Bhan Singh's water mill lying dysfunctional. |

The owner provides grinding services for wheat, maize and other locally-grown grains and keeps a small portion of the flour as a fee.

Bhan Singh used to earn around 20 kg flour daily from his two mills, which would feed his family. He even had a surplus, which he would sell in the open market. “We never calculated how much we made in monetary terms but the current rates of wheat flour is Rs 20 per kg and maize flour Rs 14-15 per kg,” he pointed out. The nine gharat owners and Hari Singh are now fighting a court case against the company.

Small is not always beautiful

Till November 30, 2011, 468 small hydel projects (upto 5MW capacity) with an aggregate capacity of 1176 MW were allotted in Himachal Pradesh. Almost all of them are run-of-the-river (RoR) projects, which diverts water through dug tunnels and then falls on the turbine from a height.

These small projects are often hailed as sustainable, non-damaging ventures and are hence exempt from submitting Environment Impact Assessment reports that are mandatory for other larger projects. The developer is also not required to hold public hearings thus preventing locals from voicing their dissent. However, these projects, scattered over several streams of the state, are closer to the people and hence impact their lives more significantly than do bigger projects.

At Sal valley of Chamba it becomes clear that issues concerning big projects are also valid for smaller ones. Project proponents extract permissions by getting a few leaders on their side, disrespect local socio-economic needs, deceive people of valid compensation and make false promises.

Legal but skewed permissions

|

| The tunnel going below the Othal village |

Due to blasts done for the tunnel, Sato’s house already shows cracks and though several requests have been made for compensation, the company has not paid any heed. Sato has now filed a court case against the company.

Dharamchand, whose fields have also been affected due to blasts, says the villagers were never consulted when a no-objection certificate was granted to the project. “Our village falls in Proutha panchayat and though we are the most affected, the panchayat pradhan gave the no-objection certification without asking us,” he claims.

The construction work has also blocked the way to nearby grazing lands thus forcing the villagers to send their livestock to higher meadows. “Around 3,000 goats and sheep have been sent for grazing which cost us Rs 25,000,” says Dharamchand.

Forgotten promises

Residents of upstream Kurtha village are happier. The Sahu Hydro Power Pvt Ltd, which is setting up a 5 MW project, paid Rs 10 lakh per bigha (each bigha equals .083 hectare) for the acquired land to 10 families. Around 40 persons have also got work as watchmen, labourers and contractors.

Though the company had promised jobs for 40 years, no written guarantee has been given on this. “They had promised to give a written agreement regarding jobs within nine months of starting the project but now it’s been three years and we have lost hope that something will come up. The project construction will finish by next month and then the work will also reduce,” says Sohanlal, who gets contracts to put together crate walls for the project.

Similar betrayals were witnessed at Paliur village where the 5.5 MW Him Kailash hydropower project has been commissioned. “First of all, they were not ready to give jobs. Later the company agreed but tried to transfer the workers to project sites in far-flung states. Thanks to a show of strength by the workers protesting such arbitrary decisions, the company had to back off,” says Lal Singh, a member of the local kisan sabha, who helped strengthen the workers’ movement.

The reward for the land acquired was one third of the market rate while compensation for 60 gharats, which dried up due to tunnelling, was never given. “Around two natural springs have dried up and water flow in four others has reduced substantially,” Singh says.

No heed to local economy

|

| Babli Devi at his farm. |

She earns Rs 3.5 lakh every year through the sale of vegetables at Chamba and Dalhousie. Sale of flowers gets her another Rs 18,000 every Diwali.

“A farmer can easily earn Rs 1-1.5 lakh annually from 2.5 bigha farmland here. Many big farmers are getting much more,” she informs. Though this may seem like a negligible amount to raise a family, Babli Devi says it’s only because of vegetable cultivation that she has been able to have a pucca house and could ensure education for her three sons.

“Till 15 years back we just managed to survive from whatever grew in the fields. With diversification into floriculture and horticulture things have really turned around. This is the story of around 24 village of this area,” she says. The positive change was also made possible because of availability of water for irrigation from the nearby stream.

Four years back, the same source was under threat as the company, Hul Hydro Power Private Limited, got approval to set up a 4.5 MW project on the stream. The project envisages diverting the stream into a 5 km-long tunnel affecting around 24,000 villagers of six gram panchayats dependent on water for farming, fishing and rearing of livestock.

People fight back

Thanks to leaders like Babli Devi, the locals gave a tough fight not only on the ground but also in the courts. Currently, the work is at a standstill and only a small road to the powerhouse site has been constructed but it was not easy to achieve this. Since the project survey started in 2007, villagers started filing objections. A protest march in 2010 turned so ugly that gun shots were fired in which several protesters were injured. After the shoot-out, the government ordered a public hearing by Additional District Magistrate where around 1,500 villagers submitted written objections against the project.

“Our local economy is totally dependent on this stream as several irrigation channels originate from it. There are around 25 watermills on its banks providing low cost grinding services to the locals. Around 2,000 trees will also be cut if the project takes off,” says Maan Singh, the pradhan of Jadera village.

Besides meeting livelihood needs, the stream is also the source of various drinking water schemes to Chamba town and nearby villages. “During the construction phase, the project will damage the water sources which feed the stream while diversion of water will also reduce the uptake for these schemes. We can’t let this happen, which is why none of the gram sabhas has given the no-objection certificate,” Singh says.

Considering all these issues, is it prudent to say that small hydel projects are also not sustainable? Dr Mohinder Slariya, who has studied socio-economic impact of dams in Himachal Pradesh, says small projects are better than the big ones but they also need to follow certain norms. “Small hydel projects are good if the developers don’t disturb the social and economic set up of local communities, involve them in decision making and follow the principle of minimum damage to ecology,” he adds. But as long as the regulatory mechanism on small projects remains lax, it’s seems like a tall order.

The CEO of Him Urja, the government agency responsible for small hydropower projects in Himachal Pradesh, did not reply to emailed queries on the issues raised in this article.

This write up was first published on India Water Portal